If you are, as I am, in your mid-fifties or older, and grew up in the United States, particularly if you lived in New England, you surely remember celebrating the nation's Bicentennial. The big celebration happened on July 4, 1976. I was seven years old, and recall marching with my Brownie troop in a local parade, wearing a Colonial-style calico dress and bonnet that my mom had sewed for me.

This is not me, but I looked a lot like the girl on the left,

in yellow, right down to the historically inaccurate footwear.

in yellow, right down to the historically inaccurate footwear.

At the time, I couldn't even imagine being alive 50 years later for the 250th anniversary, or the Sesquicentennial, celebration. "But, wait!" I hear you saying. "It's only 2025, and it's only April! You're more than a year ahead of schedule!" Ah, but July 4, 1776, the signing of the Declaration of Independence, was just the completion of the paperwork. Who cares about celebrating paperwork?!?? (Actually, having just submitted our taxes this morning, I will admit there are times when completing paperwork is celebration-worthy.) It's much more exciting to celebrate the courage of the people who began the process, the "boots on the ground" of the whole American Revolution. And THAT happened on April 19, 1775.

Thanks in large part to Schoolhouse Rock's "The Shot Heard 'Round the World," and Longfellow's poem, "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere," most American schoolchildren know that the American Revolution began in the Massachusetts towns of Concord and Lexington. We know the phrases, "The British are coming," - which was actually "The Regulars are coming out"- "Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes," and "One if by land and two if by sea." But how much do you really know about the events of that day?

I grew up in a little town in northeast Massachusetts, and I was steeped in local history. I walked Boston's Freedom Trail on numerous field trips; I watched "Johnny Tremain" in social studies class; my family visited all kinds of local and Boston museums and historical sites with out-of-town visitors. But it wasn't until I moved into the heart of it all that I really got to know the full history of that day. It began when I was living in Waltham, right next door to Lexington and Concord, and my husband somehow convinced me to get up at zero dark thirty one cold and drizzly April morning to stand on the Lexington Battle Green and watch a bunch of grown men dress up in period garb and pretend to shoot each other. Until you've experienced it, it's hard to understand the reality. Not only are there adult men, there are young boys fighting alongside them. And women and even a few girls lingering along the edges of the battle, wondering if their husbands, sons, brothers, and fathers will live through the day.

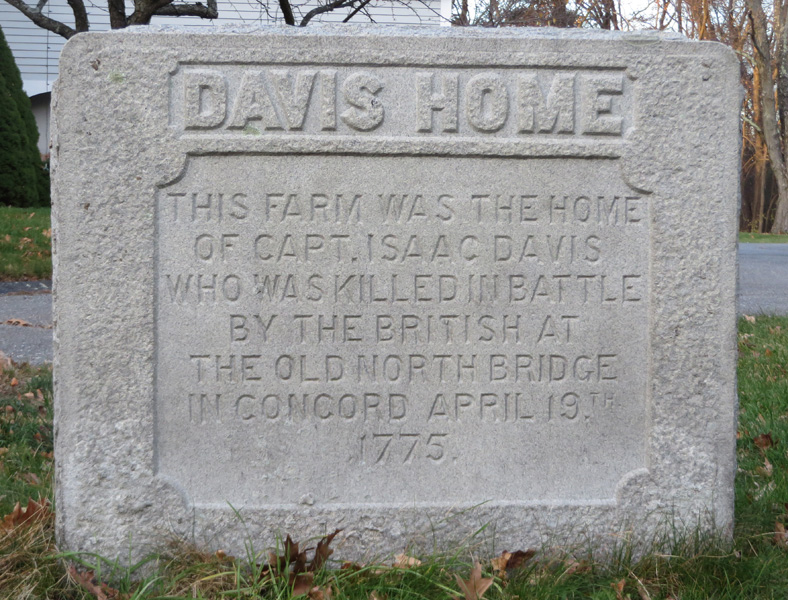

My understanding and appreciation for the brave men and women who chose to risk their lives for what they thought was right only deepened when I moved to Acton, a town which was at the heart of that initial battle. (Around here, you may hear the quote, "the battle of Lexington, fought in Concord, by men of Acton”.) We hear about "Lexington and Concord," because the first skirmishes happened on the Lexington Green and at the Old North Bridge in Concord, but Minutemen from many surrounding towns joined the fray, and the Acton Minute Company, led by Captain Isaac Davis, was among the first to respond; in fact, Captain Davis was the first American officer to fall in the Revolutionary War. When we moved to Acton, I had never heard of Isaac Davis, but there was a statue of him in the center of town, and when my son became a BSA Scout, his troop was called the "Isaac Davis Troop." One of the first Scouting events my son ever participated in was called "The Isaac Davis Trail March," which takes place annually on the Monday of Patriots' Day weekend (more about that at the end of this entry). It got me interested in the local history of the battles. Here is what happened in April 1775, from a local perspective.

On April 15, 1775, British General Thomas Gage selected 800 soldiers and planned a march for Boston to the town of Concord, planning to capture or destroy a stockpile of weapons and ammunition that was rumored to be stored there. American spies got wind of the plan, and couriers spread the alarm to surrounding towns to put the local minutemen on alert, although they did not yet know the timing of the march. On the morning of April 18th, Gage sent ten soldiers to patrol the road between Boston and Concord and intercept any messengers heading for Concord, but the word had already gone out. The cannons and other heavy equipment that were, in fact, stored in Concord, had been quickly spirited away to other towns, including two brass mortars which were sent to the nearby town of Acton. At 10pm on April 18th, the British soldiers set off in long boats to cross Boston Harbor to Lechmere Point, wading through the marshlands and then setting off towards Lexington and Concord.

When the Americans realized the march had begun, they dispatched two riders to alert the residents of nearby towns. William Dawes was to ride through Roxbury, Brookline, and Harvard Square, and Paul Revere was to ride from Charlestown through Medford and Menotomy (now Arlington) to Lexington and towns to the west. The Americans knew that the British had two options to get from Boston to Concord: they could march across Boston Neck on foot, or they could cross the Charles River by boat. Revere crossed Boston Harbor, looking for the pre-arranged signal from the Old North Church, with one lantern signaling the overland route and two the boat route ("One if by land and two if by sea"). Two lanterns were visible, so when Revere arrived in Lexington, he was able to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock of the imminent arrival of the British from across the Harbor. Half an hour later Dawes arrived and the two left to carry the alarm to Concord, and were joined on the outskirts of Lexington by Dr. Samuel Prescott. Halfway to Concord, at around midnight, they were intercepted by a British unit, who herded them into a field bordered by a stone wall. Prescott's horse was able to jump the wall and he escaped, continuing to raise the alarm (as the citizens spread the word via gunfire and the ringing of church bells) through the towns of Lincoln, Concord, Acton, and Stow. Dawes also escaped, but Revere was captured. (I suspect that the only reason Revere is more famous than the others is that Longfellow found the name "Revere" much easier to rhyme than either "Dawes" or "Prescott.")

A town of about 750 residents, Acton had three companies of Minutemen, the most zealous being led by Captain Isaac Davis. The company drilled twice a week, accompanied by fifer Luther Blanchard and drummer Francis Barker, who often played "The White Cockade," which came to be the company's signature tune. The company was somewhat unusual in that all their rifles had bayonets, many of which had been made by Davis himself. Hearing the alarm, 37 members of Davis' company mustered at his home, where Davis formed them into two columns and they began the 7-mile march to Concord. They were heading for the Concord Common, where they had mustered in the past, until they received word that Colonel James Barrett, the Concord militia commander, had ordered his men to Punkatasset Hill on the west side of the Concord River, so the Acton Company headed for the North Bridge to join them.

While this was going on, the men of Lexington were gathering at Buckman’s Tavern, expecting the British to pass through on their way to Concord. The British troops arrived at about 5:00am and were met by a company of more 70 men led by Captain John Parker. The British rushed forward and Parker ordered his men to disperse, but at some point a shot rang out (it was never clear which side shot first, both sides having been ordered not to engage) and the British soldiers opened fire on the Minutemen, killing seven and mortally wounding one, then continued on to Concord. When they arrived at the North Bridge at around 8:00am, , they left part of their troops to guard the bridge and sent another part to raid Barrett's farm and burn the supplies that were rumored to be stored there. The colonial officers held a council of war, and seeing smoke rising from the town of Concord, agreed to advance over the bridge and confront the British in an effort to save the town. Barrett ordered Major John Buttrick to cross the bridge, but not to fire unless fired upon. Buttrick asked a Concord captain to lead the march, but he declined. Buttrick then asked Captain Davis if he was afraid to go, and Davis replied, “No, I am not, and I haven’t a man that is afraid to go.” Davis’ men marched toward the bridge, followed by companies from Concord, Bedford, Lincoln, and others from Acton.

As they approached, the British soldiers retreated, leaving behind a few men to try to destroy the bridge, but they soon fell back with the rest of the British troops. As the Americans continued to approach, the British soldiers fired a few shots, and several Americans were slightly wounded. Buttrick ordered his men to fire back, reportedly shouting, "For God's sake, fire!", but only Davis' company was in a position to do so. Davis was killed and another American mortally wounded during the ensuing volley (now known as "the shot heard 'round the world," thanks to Ralph Waldo Emerson, despite the fact that the exchange of fire in Lexington happened first), and a few British soldiers were also killed or wounded. The British retreated with a handful of Americans at their heels, although most returned to the bridge. Despite the arrival of British reinforcements from Concord, and there was no further fighting there.

Other American troops continued to assemble at the Concord muster field, and, fearing his force would be outnumbered, the British commander ordered his men to retreat, firing on the colonial soldiers who fired on them from behind trees and stone walls from nearby Meriam's Corner all the way back to Charlestown, 16 miles away, a route now known as "Battle Road". At Lexington, the British were met by reinforcements. They pillaged and burned part of the town, killing some civilians, before continuing on towards Boston. At Menotomy, they were attacked by colonists who now outnumbered them two to one, suffering significant casualties.

With 243 men dead, wounded, or missing, the British barely reached Boston by sundown, and the Siege of Boston began. A force of 20,000 colonists from across the region pinned the British forces within the city of Boston for 11 months, a siege that ended with George Washington’s capture of Dorchester Heights. The occupying British troops finally left Massachusetts for good in March of 1776.

A Note on the Isaac Davis Trail March:

In 1957, Acton's Boy Scout (now BSA) Troop began a tradition of hiking the 7-mile route from Acton to the Old North Bridge in Concord, a tradition that continues to this day. Historical reenactors posing as the Acton Minute Company muster at the Isaac Davis House in Acton and march to the Old North Bridge, keeping as close as possible to the original route and timeline. Members of Troop 1 Acton (the Isaac Davis Troop) follow the reenactors, as do members of other local BSA Troops, and the public is invited to join them along the trail as well.

References:

https://actonminutemen.org/isaacdavistrail/

https://isaacdavis.org/history-links/

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/patriotsday-key-places-april-18-19-1775/

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/lexington-and-concord

https://issuu.com/discoverconcordma/docs/dc.spring21.final/s/11973717

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/americanrevolution/timeline.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment